Listening to a Phillip Glass piece is more  like studying a stained glass window than listening to music in the conventional sense  – a passing glance would only tell part of the story, while the full picture is revealed by standing in deep meditation of its nuances.  Originally purchased tickets for last night’s Zellerbach performance of Einstein on the Beach back in June, but didn’t realize until a few days ago that I had signed us up for a 4.5-hour performance (“not including opening tones”). Even though I’ve got a warm spot in my heart for Glass, and had always been curious to see Robert Wilson’s legendary 1975 “Opera in four parts,” started to worry I had signed us up for  4+ hours of “difficult listening hour.” It’s not that Glass’ music is “difficult” per se’, but that he works in such large arcs, often pushing the limits of what audiences are willing to sit through. That doesn’t mean his work isn’t gorgeous – it is – but that we have to reorient our expectations of how long a composition should last, how willing we are to slow the hell down and become absorbed in a slow progression of subtly shifting notes and chords.

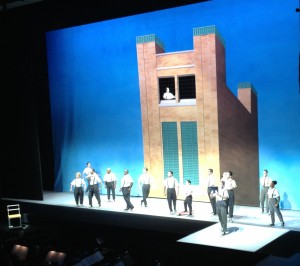

The “opera” (Glass says he only considers it an opera when it’s performed in an opera house … otherwise, “it is what it is”) is a meditation on science and society, gender roles, habits, patterns of living, all slowly unfolding as semi-opaque vignettes. The scene pictured above, for example, took twenty minutes to unpack. It is not just frozen because it’s a photograph – it’s frozen by composition. Starting as an impeccably painted factory building with a sole figure in the top window, characters (stereotypes) slowly enter and freeze into position. So little happens, it was almost painful to watch (though gorgeous to hear). But the funny thing about these “knee plays” is that every time you feel like your patience has been stretched to its limit, you realize that you’re  totally fascinated. Small details become important.

![albert-einstein-at-beach-1945[2]](http://stuckbetweenstations.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/albert-einstein-at-beach-19452-214x300.jpeg) In another scene, a 30-foot-long bar of pure white light lays horizontally on the stage in the dark. As the music builds, one end of it slowly lifts up, moving so slowly it’s barely perceptible. A line is becoming an angle – that’s all – and over the course of 10 minutes, the bar finally reaches its vertical zenith. “Good,” you think, “Let’s move on.” Then the now-vertical bar starts to rise, and you realize it’s going to take another 10 minutes for it to ascend up behind the curtains. Part of you is asking “Are you kidding me? You’ve got to be kidding me.” while another part of you is totally absorbed in the movement of the simple light, thinking “So this is what the passage of time feels like.” You just have to let go of your rock and roll expectations and allow yourself to be swept into the pace of Glass – there is no other way.

In another scene, a 30-foot-long bar of pure white light lays horizontally on the stage in the dark. As the music builds, one end of it slowly lifts up, moving so slowly it’s barely perceptible. A line is becoming an angle – that’s all – and over the course of 10 minutes, the bar finally reaches its vertical zenith. “Good,” you think, “Let’s move on.” Then the now-vertical bar starts to rise, and you realize it’s going to take another 10 minutes for it to ascend up behind the curtains. Part of you is asking “Are you kidding me? You’ve got to be kidding me.” while another part of you is totally absorbed in the movement of the simple light, thinking “So this is what the passage of time feels like.” You just have to let go of your rock and roll expectations and allow yourself to be swept into the pace of Glass – there is no other way.

Wilson’s stage production is austere, lightly symbolic, and sometimes funny, while the patience and endurance of the performers is stunning. It was the job of one dancer to “read” through much of the evening. Wearing  gray slacks, suspenders, and a white Oxford, she held a stiff book full of blank pages. Her head shook rapidly from side to side, vibrating  like a bobble-head doll, as if stuck in a permanent speed-reading trance. But reading what? That’s not important. It’s like she was the abstract, Platonic form of a reader, reading the abstract, Platonic form of a book. Nothing more, nothing less. How she maintained that head-wobbling for so long is beyond me – our necks ached in sympathy.

The performance peaks  in a crescendo of light and movement dedicated to the atomic age (the Einstein connection). A scaffolding rig recreates the Hollywood Squares of performance art, with dancers gesticulating mathematically at dancing light displays, some squares  shared with musicians. Lucite boxes containing floating, writhing humans traverse slowly from side to side. The victim of a nuclear blast dances with flashlights in the foreground. Two people crawl out of plastic domes, then slowly “duck and cover” to shield themselves from an atomic blast. An immense, gauzy scrim is lowered in front of it all – a massive enlargement of a 1950s explainer diagram on the mechanics of atomic detonation.

All the while, a violinist in an Einstein costume sites in a lonely chair in front of the stage, above the orchestra pit, playing his heart out just for you.

4.5 hours later we wandered outside into a warm October Berkeley evening, wondering where the time had gone.

Listening experience flow chart by Amy Kubes: Â Life Cycle of a Phillip Glass PieceÂ

Is this the one where they song nonsense syllables for so long that yor mind starts to hallucinte hearing words?

Great coverage. I love Ms. Kubes’ chart!

agh ipad typos!

xian – Yes, that’s the one. Lots of mellifluous nonsense syllables. But Glass got nothing on Tristan Tzara. Tuff-M, i Zimbra!

ah, the violinist was a woman! At the morning lecture, Wilson and Glass suggested that the audience must complete the work, because of so much ambiguity (and no beach!). They also said specifically that lots of bloggers would go home and immediately post mini-reviews, but that fully understanding the experience would happen only after a week or two of absorption.

Hugh, sounds like the lecture was really worth hearing. Funny that they predicted the mini-reviews on blogs. And yes, they were right that I’ll still be absorbing for a while to come.

You’re right that the violinist was a woman – I waffled on whether to refer to the gender of the actor/player or of Einstein in that sentence…