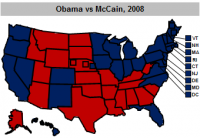

For months, I’ve wondered what music I’d want to listen to once the long election march toward the post-Bush era was finally over. The always-reliable Carrie Brownstein had some great pre-election suggestions in her Monitor Mix blog —the Chambers Brothers’ “Time Has Come Today,†Al Green’s version of Curtis Mayfield’s “People Get Readyâ€â€”but like me, she found that on election night the only real answer was to make your own music. From NYC’s Union Square, she reported “magically becoming tolerant†of “the Bacchanalia I usually associate with drum circles, Hemp Fests and Renaissance Fairs.†Fresh off the plane from two days of voter protection work in Nevada, I had a similar moment, banging on an assortment of random percussion instruments with my three year-old son Matthew like a giddy hippie who’d staggered through one too many Dead tours asking for a miracle.

For months, I’ve wondered what music I’d want to listen to once the long election march toward the post-Bush era was finally over. The always-reliable Carrie Brownstein had some great pre-election suggestions in her Monitor Mix blog —the Chambers Brothers’ “Time Has Come Today,†Al Green’s version of Curtis Mayfield’s “People Get Readyâ€â€”but like me, she found that on election night the only real answer was to make your own music. From NYC’s Union Square, she reported “magically becoming tolerant†of “the Bacchanalia I usually associate with drum circles, Hemp Fests and Renaissance Fairs.†Fresh off the plane from two days of voter protection work in Nevada, I had a similar moment, banging on an assortment of random percussion instruments with my three year-old son Matthew like a giddy hippie who’d staggered through one too many Dead tours asking for a miracle.

By the next morning, though, I knew exactly what I wanted to hear. On his unlikely path to the Presidency, Barack Obama kept his cool very much like vintage late fifties/ early sixties Miles Davis. Like Obama, the Miles who recorded Kind of Blue was hardly a radical; his subtle power was less iconoclastic than Ornette Coleman’s similarly timed Shape of Jazz to Come and less dramatic than the Giant Steps of his sideman John Coltrane. Yet Miles too was a forward thinker who nailed his moment in history. Sensing that hard bop’s routine of riffing had become a bridge to nowhere, he dispensed with straight chord progressions in favor of modes and shaped sounds that still seem almost as fresh as they did nearly half a century ago. After enduring a parade of hotheads, blowhards, dimwits, and trigger-happy supermodels, I’ll spend today celebrating the simple virtues of the “coolâ€â€”not in the snarky sense of “hipper than thou,†but as a credo standing for resilient grace and poise in the face of chaos.

As an occasional hothead, I can’t help wondering whether the cool President-Elect Obama who channels mid-period Miles also has a little Bitches’ Brew bubbling under the surface. Before I could even complete this thought, I discovered that someone has already done a mash-up of Obama’s speeches and electric Miles, notably “Feio” from the Bitches’ Brew sessions. There’s a new deal in town, and I can’t wait to listen.

Miles Davis, “So What” (featuring John Coltrane)

Barack Obama can’t even do an interview anymore without having to address one of his least-favorite subjects: the suspicion that beneath his calm demeanor and business-suited exterior, he is a fanatical Pink Floyd fan. The long-simmering suspicions boiled over last week at California’s Coachella Music Festival. Former Floyd leader Roger Waters arranged an unauthorized

Barack Obama can’t even do an interview anymore without having to address one of his least-favorite subjects: the suspicion that beneath his calm demeanor and business-suited exterior, he is a fanatical Pink Floyd fan. The long-simmering suspicions boiled over last week at California’s Coachella Music Festival. Former Floyd leader Roger Waters arranged an unauthorized  Hillary Clinton noted that “there is no clear evidence that Barack Obama is an America-hating Pink Floyd fanatic. As far as I know.†“But let me tell you,†she continued, “during my administration, we’ll have no time for laser light shows, ponderous guitar solos, vague anti-capitalist lyrics, and

Hillary Clinton noted that “there is no clear evidence that Barack Obama is an America-hating Pink Floyd fanatic. As far as I know.†“But let me tell you,†she continued, “during my administration, we’ll have no time for laser light shows, ponderous guitar solos, vague anti-capitalist lyrics, and