About Roger Moore

Roger Moore is a writer and musical obsessive who plays percussion instruments from around the world with an equal lack of dexterity. An environmental lawyer in his unplugged moments, he has written on subjects ranging from sustainable development practices to human rights and voting rights, as well as many music reviews. A native Chicagoan, Roger lives in Oakland, California with his wife Paula, who shares his Paul Weller fixation, and two young children, Amelia and Matthew, who enjoy dancing in circles to his Serge Gainsbourg records and falling asleep to his John Coltrane records.

Roger Moore is a writer and musical obsessive who plays percussion instruments from around the world with an equal lack of dexterity. An environmental lawyer in his unplugged moments, he has written on subjects ranging from sustainable development practices to human rights and voting rights, as well as many music reviews. A native Chicagoan, Roger lives in Oakland, California with his wife Paula, who shares his Paul Weller fixation, and two young children, Amelia and Matthew, who enjoy dancing in circles to his Serge Gainsbourg records and falling asleep to his John Coltrane records.

Roger Moore’s Musical Timeline

1966. Dropped upside down on patio after oldest sister listened to “She Loves You†on the Beatles’ Saturday cartoon show. Ears have rung with the words “yeah, yeah, yeah†ever since.

1973. Memorized all 932 verses to Don McLean’s “American Pie.â€

1975. Unsuccessfully lobbied to have “Louie Louie†named the official song of his grade school class. The teacher altered the lyrics of the winner, the Carpenters’ “I Won’t Last a Day Without You,†so that they referred to Jesus.

1977. After a trip to New Orleans, frequently broke drumheads attempting to mimic the style of the Meters’ Zigaboo Modeliste.

1979. In order to see Muddy Waters perform in Chicago, borrowed the birth certificate of a 27 year-old truck driver named Rocco.

1982. Published first music review, a glowing account of the Jam’s three-encore performance for the Chicago Reader. Reading the original, unedited piece would have taken longer than the concert itself.

1982. Spat on just before seeing the Who on the first of their 23 farewell tours, after giving applause to the previous band, the Clash.

1984. Mom: “This sounds perky. What’s it called?†Roger: “ It’s ‘That’s When I Reach for My Revolver’ by Mission of Burma.â€

1985. Wrote first review of an African recording, King Sunny Ade’s Synchro System. A reader induced to buy the album by this review wrote a letter to the editor, noting that “anyone wishing a copy of this record, played only once†should contact him.

1985. At a Replacements show in Boston, helped redirect a bewildered Bob Stinson to the stage, which Bob had temporarily confused with the ladies’ bathroom.

1986. Walked forty blocks through a near-hurricane wearing a garbage bag because the Feelies were playing a show at Washington, D.C.’s 9:30 Club.

1987. Foolishly asked Alex Chilton why he had just performed “Volare.†Answer: “Because I can.â€

1988. Moved to Northern California and, at a large outdoor reggae festival, discovered what Bob Marley songs sound like when sung by naked hippies.

1991. Attempted to explain to Flavor-Flav of Public Enemy that the clock hanging from his neck was at least two hours fast.

1992. Under the pseudonym Dr. Smudge, produced and performed for the Underwear of the Gods anthology, recorded live at the North Oakland Rest Home for the Bewildered. Local earplug sales skyrocketed.

1993. Attended first-ever fashion show in Chicago because Liz Phair was the opening act. Declined the complimentary bottles of cologne and moisturizer.

1997. Almost missed appointment with eventual wedding band because Sleater-Kinney performed earlier at Berkeley’s 924 Gilman Street. Recovered hearing days later.

1997. After sharing a romantic evening with Paula listening to Caetano Veloso at San Francisco’s Masonic Auditorium, purchased a Portuguese phrasebook that remains unread.

1998. Learned why you do not yell “Free Bird†at Whiskeytown's Ryan Adams in a crowded theater.

1999. During an intense bout of flu, made guttural noises bearing an uncanny resemblance to the Throat Singers of Tuva.

2000. Compiled a retrospective of music in the nineties as a fellow at the Coolwater Center for Strategic Studies and Barbecue Hut.

2001. Listened as Kahil El’Zabar, in the middle of a harrowing and funny duet show with Billy Bang, lowered his voice and spoke of the need to think of the children, whom he was concerned might grow up “unhip.â€

2002. During a performance of Wilco’s “Ashes of American Flags,†barely dodged ashes of Jeff Tweedy’s cigarette.

2002. Arrived at the Alta Bates maternity ward in Berkeley with a world trance anthology specially designed to soothe Paula during Amelia’s birth, filled with Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Ali Akbar Khan, and assorted other Khans. The project proved to be irrelevant to the actual process of labor.

2003. Emceed a memorable memorial concert for our friend Matthew Sperry at San Francisco’s Victoria Theater featuring a lineup of his former collaborators, including improvised music all-stars Orchesperry, Pauline Oliveros, Red Hot Tchotchkes, the cast of Hedwig and the Angry Inch, and Tom Waits.

2003. Failed to persuade Ted Leo to seek the Democratic nomination for President.

2005. Prevented two-year old daughter Amelia from diving off the balcony during a performance of Pierre Dorge’s New Jungle Orchestra at the Copenhagen Jazz Festival.

2006. On a family camping trip in the Sierra Nevadas, experienced the advanced stage of psychosis that comes from listening to the thirtieth rendition of Raffi’s “Bananaphone†on the same road trip.

View all posts by Roger Moore →

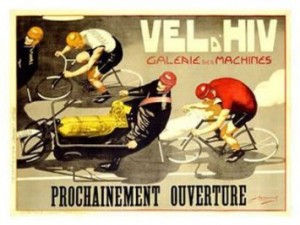

A few weeks ago, I started pulling together a bicycle-themed playlist. I’d hoped it would motivate me to train for a late-April metric century bike ride in Chico, California, which due to some feat of bike snobbery or hippie irony is known as the Mildflower.

A few weeks ago, I started pulling together a bicycle-themed playlist. I’d hoped it would motivate me to train for a late-April metric century bike ride in Chico, California, which due to some feat of bike snobbery or hippie irony is known as the Mildflower.

One thought on “Vel’ d’Hiv: Springtime for Hitler (and Bicycles)”

Comments are closed.