Part One: Life During Wartime

Last week, when Aretha Franklin put on her oversized bow hat and melted fire with her inaugural version of “America (My Country ‘Tis of Thee)â€â€”Samuel Francis Smith’s 19th Century rewrite of a German rewrite of “God Save the Queenâ€â€”a piece of my heart held the memory of another queen of soul, one generation and half a world away, who met with a more tragic fate. Blessed with a voice of equally staggering power and beauty, Ros Sereysothea rose from poverty and illiteracy to become the most beloved singer in her native Cambodia during the sixties and early seventies. Thanks to the excellent Los Angeles combo Dengue Fever, discussed below, the music of Ros and her contemporaries is finally experiencing a rebirth on both sides of the Pacific.

Last week, when Aretha Franklin put on her oversized bow hat and melted fire with her inaugural version of “America (My Country ‘Tis of Thee)â€â€”Samuel Francis Smith’s 19th Century rewrite of a German rewrite of “God Save the Queenâ€â€”a piece of my heart held the memory of another queen of soul, one generation and half a world away, who met with a more tragic fate. Blessed with a voice of equally staggering power and beauty, Ros Sereysothea rose from poverty and illiteracy to become the most beloved singer in her native Cambodia during the sixties and early seventies. Thanks to the excellent Los Angeles combo Dengue Fever, discussed below, the music of Ros and her contemporaries is finally experiencing a rebirth on both sides of the Pacific.

Ros’s story carries a distinctive rock twist. Along with the cherub-faced godfather of Khmer soul, Sinn Sisamouth, a former Royal Court crooner turned unlikely garage rocker, and the more playful female vocalist Pan Ron, who makes me think of Martha Reeves, Ros meshed Khmer music with the range of Western sounds that made their way across the Pacific during wartime—everything from Motown and classic R&B to surf, psychedelic and garage rock. Eastern sounds from Bangkok to Bollywood also entered the mix. The resulting Khmer rock underground was like nothing else heard before or since. A track like Ros’s “Chnam Oun 16†(translated as “I’m 16†or “Sweet 16â€) virtually defies description, but to me it sounds a bit like an even more intense Asha Bhosle performing an upbeat Aretha number, backed by the 13th Floor Elevators. The song sounds so alive that it seems to mock death itself for its weakness and cowardice.

Ros Sereysothea, “Chnam Oun 16”

As John Swain captured in his Indochina memoir River of Time, Khmer rock’s seminal figures remained upstarts in their heyday; even Ros and Sinn scrounged for cassette sale revenue and never reached the upper echelons of Cambodia’s economic elite. But their musical revolution came to an abrupt end after April 1975, when Pol Pot’s forces overrode Cambodia. Few of the leading Khmer musicians survived the genocide. Sinn Sisamouth was sent to a work camp and executed. Pan Ron disappeared. Ros Sereysothea’s demise remains the subject of conjecture, but Greg Cahill’s short film about her life, The Golden Voice, concludes that after her discovery in a slave labor camp, she was forced to sing pro-Khmer Rouge songs and marry one of Pol Pot’s henchmen, who later had her killed. In another account, she died from malnutrition in a Phnom Penh hospital weeks before the Vietnamese invasion ousted Pol Pot. Either way, this achingly beautiful and surprisingly rocking music—which often paired melancholy sentiments with sparkling melodies—virtually disappeared, preserved only because fans risked lives and livelihoods hiding priceless cassette tapes. The musical history of a generation went undercover in the face of what Hannah Arendt, commenting on a different genocide, termed “the banality of evilâ€: ordinary people following orders confiscated and destroyed the tapes, even as they were silently humming these same songs under their breath.

As John Swain captured in his Indochina memoir River of Time, Khmer rock’s seminal figures remained upstarts in their heyday; even Ros and Sinn scrounged for cassette sale revenue and never reached the upper echelons of Cambodia’s economic elite. But their musical revolution came to an abrupt end after April 1975, when Pol Pot’s forces overrode Cambodia. Few of the leading Khmer musicians survived the genocide. Sinn Sisamouth was sent to a work camp and executed. Pan Ron disappeared. Ros Sereysothea’s demise remains the subject of conjecture, but Greg Cahill’s short film about her life, The Golden Voice, concludes that after her discovery in a slave labor camp, she was forced to sing pro-Khmer Rouge songs and marry one of Pol Pot’s henchmen, who later had her killed. In another account, she died from malnutrition in a Phnom Penh hospital weeks before the Vietnamese invasion ousted Pol Pot. Either way, this achingly beautiful and surprisingly rocking music—which often paired melancholy sentiments with sparkling melodies—virtually disappeared, preserved only because fans risked lives and livelihoods hiding priceless cassette tapes. The musical history of a generation went undercover in the face of what Hannah Arendt, commenting on a different genocide, termed “the banality of evilâ€: ordinary people following orders confiscated and destroyed the tapes, even as they were silently humming these same songs under their breath.

Sinn Sisamouth, “Ma Pi Noak”

Pan Ron, “Rom Ago Ago”

After the click-through: Dengue Fever and the renaissance of Khmer rock and roll.

Part Two: Dengue Fever and the Khmer Rock Renaissance

For years, the golden age of Khmer rock remained virtually unknown in the west. The occasional exceptions included Parallel World’s 1996 Cambodian Rocks anthology (first released without any artist or track information), and the several classic tracks that appeared in the soundtrack to the 2002 film City of Ghosts. But the music’s renaissance is largely due to Dengue Fever, whose uncharacteristically mellow Khmer language cover of Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now†was featured in City of Ghosts. The band has one of the more improbable histories in recent memory. Ethan Holtzman, a California-based keyboardist, traveled to Cambodia in the 1990s, and while his traveling companion was contracting dengue fever, he was filling his backpack with classic Khmer cassettes. Inspired to form a band performing Cambodian rock covers, he recruited several stellar musicians, including his brother Zac, the former Dieselhead guitarist who should have won last month’s battle of the beards. Traversing the karaoke clubs of Long Beach, California’s Little Phnom Penh, they became entranced by a beguiling young singer, Chhom Nimol, who had already become a teenage sensation back in Cambodia. Incredibly, they persuaded her to join the band, which has progressed from a Cambodian covers-only format to equally impressive original material that brings in everything from homegrown California psych-pop to Ethiopian jazz.

For years, the golden age of Khmer rock remained virtually unknown in the west. The occasional exceptions included Parallel World’s 1996 Cambodian Rocks anthology (first released without any artist or track information), and the several classic tracks that appeared in the soundtrack to the 2002 film City of Ghosts. But the music’s renaissance is largely due to Dengue Fever, whose uncharacteristically mellow Khmer language cover of Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now†was featured in City of Ghosts. The band has one of the more improbable histories in recent memory. Ethan Holtzman, a California-based keyboardist, traveled to Cambodia in the 1990s, and while his traveling companion was contracting dengue fever, he was filling his backpack with classic Khmer cassettes. Inspired to form a band performing Cambodian rock covers, he recruited several stellar musicians, including his brother Zac, the former Dieselhead guitarist who should have won last month’s battle of the beards. Traversing the karaoke clubs of Long Beach, California’s Little Phnom Penh, they became entranced by a beguiling young singer, Chhom Nimol, who had already become a teenage sensation back in Cambodia. Incredibly, they persuaded her to join the band, which has progressed from a Cambodian covers-only format to equally impressive original material that brings in everything from homegrown California psych-pop to Ethiopian jazz.

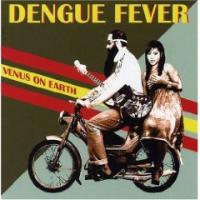

If you simply listened to Dengue Fever’s hilarious 2008 ode to troubled transcontinental romance, “Tiger Phone Card,†you might think that Dengue Fever was merely a really good international novelty act. But as shown on most of the recent Venus on Earth album, the band deserves better than to be consigned to the “world music†ghetto. A rock band every bit as much as Radiohead or TV on the Radio, Dengue Fever serves as a reminder that, due to the prominent American R&B and rock influence, the lost years of Cambodian rock are also a lost part of our own collective memory deserving of rebirth.

If you simply listened to Dengue Fever’s hilarious 2008 ode to troubled transcontinental romance, “Tiger Phone Card,†you might think that Dengue Fever was merely a really good international novelty act. But as shown on most of the recent Venus on Earth album, the band deserves better than to be consigned to the “world music†ghetto. A rock band every bit as much as Radiohead or TV on the Radio, Dengue Fever serves as a reminder that, due to the prominent American R&B and rock influence, the lost years of Cambodian rock are also a lost part of our own collective memory deserving of rebirth.

John Pirozzi, the director whose film Sleepwalking Through the Mekong chronicles Dengue Fever’s surreally rewarding 2005 tour in Cambodia, is working on a broader movie called Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten on the lost history of Cambodian rock and roll. Four volumes of Cambodian Rocks reissues are available on the Khmer Rocks label, and a wealth of Khmer rock classics are also available on YouTube and elsewhere on the net. These efforts bear witness to the stunning musical contributions of a strife-torn country, intertwined with our own tangled war-torn history, deserving recognition for something richer and grander than killing fields and donut shops. Rather than retreating in the face of evil, past or present, we have the opportunity to become educated about our country’s complex history in southeast Asia, while also cranking up the volume and letting freedom ring.

Dengue Fever, “Tiger Phone Card”

Dengue Fever, “Sleepwalking Through the Mekong”

Dengue Fever, “Seeing Hands”

Dengue Fever, “I’m 16”

Wondering if there’s a back-story behind that giant kick-drum/human-sized gong behind the guitarist in the Sleepwalking clip. I love the pace of that track, the way it rolls like clouds (a weird comparison I know, but Van Morrison sometimes nailed that rolling pace… you could just glide on; but this is so much more organic than Van).

Amazing stuff Roger. I have Venus on Earth, but now realize I hadn’t given the time it deserves.

Looks like there’s a documentary DVD about the band out now.

Covered on Very Short List

At NetFlix