A short trip to Austin earlier this month felt like a homecoming, even though I’ve never been there before. I’ve rarely been bombarded with so much music, with so little planning or effort, for so long into the night, since I left Chicago for California more than two decades ago. Austin is the sort of place where you venture out for coffee after your night of music and find out that the coffeehouse (in this case, Jo’s Hot Coffee on South Congress) has its own house band playing a bang-up set of western swing. A record store mural across the street from the UT/ Austin campus registers the city’s sense of music history: among others, Buddy Holly, Willie Nelson and Johnny Cash share wall space with Dylan, Iggy, and the Clash.

A short trip to Austin earlier this month felt like a homecoming, even though I’ve never been there before. I’ve rarely been bombarded with so much music, with so little planning or effort, for so long into the night, since I left Chicago for California more than two decades ago. Austin is the sort of place where you venture out for coffee after your night of music and find out that the coffeehouse (in this case, Jo’s Hot Coffee on South Congress) has its own house band playing a bang-up set of western swing. A record store mural across the street from the UT/ Austin campus registers the city’s sense of music history: among others, Buddy Holly, Willie Nelson and Johnny Cash share wall space with Dylan, Iggy, and the Clash.

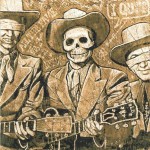

If one figure spans all those influences, it is the provocateur, painter, raconteur and raver Jon Langford. The Welsh-born Leeds-to-Chicago transplant and Bloodshot Records mainstay has—in the 23-year stretch dating from the Mekons’ often-mentioned, seldom heard Fear and Whiskey—done more than just about anyone else to resuscitate the withered heart of post-punk and reclaim the tarnished soul of American country. In Austin, I was thrilled to discover that the Yard Dog Gallery has a fantastic collection of Langford’s visual art, mostly densely layered, distressed images of iconic American roots musicians in graveyard settings. Blindfolded, sullied and marked for extinction, the characters remind me of Chicago artist Ivan Albright’s studies of decay and corruption; constantly “dancing with death,†they are unsettlingly alive and a reminder of the slow death that comes out of greed, fear and homogenization.

As a curmudgeonly first-generation art school punk who writes lines like “John Glenn drinks cocktails with God at a café in downtown Saigon,†Langford is smart enough to realize he doesn’t play or paint “authentic†honky tonk any more than Vampire Weekend is a gang of African tribesmen. And unlike some of his retro-worshipping peers, he acknowledges that the “golden age†of county music had its own problems with pills and pretenders and poor directions. Yet he uses his outsider’s distance as an advantage. While bemoaning the death of country music at the hands of what he calls “suburban rock music with a cowboy hat on,†Langford’s work cuts deeper than that, excavating the signs of life in a cultural landscape pockmarked with interchangeable strip malls and Kenny Chesney records. There’s also a redemptive element in the search; like his protagonist in his Waco Brothers anthem “Hell’s Roof,†he’s reclaiming a lost history, “walking on hell’s roof, looking at the flowers†(and not “walking in a clown suit, looking at the flowers,†as I misheard Langford’s impassioned growl for more than a year).

Jon Langford, “Hell’s Roofâ€

Many of Langford’s paintings are collected in Langford’s 2006 book Nashville Radio: Art, Words and Music, which intersperses his artwork with lyrics and some unforgettable stories. One of my favorites involves Jon and the gang in East Berlin just before the wall fell, unable to buy souvenir Stalinist bric-a-brac with their worthless East German marks; another, during their short brush with near-fame following the release of 1989’s Mekons Rock and Roll, found A&M cofounder/ vice-chairman Herb Alpert’s secretary forging an autograph on a CD for Langford’s mother: “Dear Mrs. Langford, you have a fine and talented son—Herb Alpert†(sadly, Alpert himself was never present to shower them in whipped cream and other delights).

Many of Langford’s paintings are collected in Langford’s 2006 book Nashville Radio: Art, Words and Music, which intersperses his artwork with lyrics and some unforgettable stories. One of my favorites involves Jon and the gang in East Berlin just before the wall fell, unable to buy souvenir Stalinist bric-a-brac with their worthless East German marks; another, during their short brush with near-fame following the release of 1989’s Mekons Rock and Roll, found A&M cofounder/ vice-chairman Herb Alpert’s secretary forging an autograph on a CD for Langford’s mother: “Dear Mrs. Langford, you have a fine and talented son—Herb Alpert†(sadly, Alpert himself was never present to shower them in whipped cream and other delights).

The Nashville Radio book also comes with a thoroughly enjoyable 18-song CD, The Nashville Radio Companion Earwig, which contains powerful acoustic renditions of some of Langford’s most striking country-related songs, supported by a strong cast of Langford comrades including singer Sally Timms, bassist Tony Maimone, and violinist Jean Cook. Earwig is an indispensable treat if, like me, you find it too daunting to keep up with every release of Langford’s many groups (to name a few, the Three Johns, the Waco Brothers, the Pine Valley Cosmonauts, the Sadies, Ship and Pilot, and even a children’s music band, the Wee Hairy Beasties). Keeping up with these could be a full-time job. The Waco Brothers just put out Waco Express, a first-rate live album recorded in Chicago. On April 27, Victory Gardens in Chicago will debut a theatrical version of Langford’s 2004 solo concept album, All the Fame of Lofty Deeds.

All of Jon Langford’s bleak musing about commerce and decaying culture could come off as misanthropic and pretentious if he didn’t spend most of his time being genial and side-splittingly funny. If you find yourself in a Langford book-buying mood, don’t miss his amazing turn (under the moniker Chuck Death) as the illustrator of the cynical, hilarious and usually dead-on music criticism cartoon book Great Pop Things, penned by his Pythonesque partner in crime Colin B. Morton. In its only slightly fictionalized history, the bass player in Led Zeppelin was Jean-Paul Sartre. Brian Eno is credited with the creation of “ambivalent music, which you can’t quite tell if you are listening to it or not.†Bono gets mercilessly tweaked, and Morrissey takes it on the chin more than once. Robert Christgau reports that at the EMP Conference, Langford defended himself against charges of cynicism by saying, “We really like all these people. Except Sting, of course.â€

Mekons, “Ghosts of American Astronautsâ€

Mekons, “Memphis Egyptâ€

Waco Brothers, “Death of Country Musicâ€

Wow – If you close your eyes, you can hear a lot of Joe Strummer in Langford’s voice (referring to the Waco Bros. clip).

Was/is Herb Alpert really the chairman of A&M? That’s just too poetic for words. I feel like the circular sticker in the middle of an A&M LP is indelibly associated with Herb Alpert records already – this factoid seals the deal.

Langford’s voice also makes me think of Strummer. Oddly enough, the Mekons’ first big song was “Never Been in a Riot,” an even cruder parody of the Clash’s “White Riot.”

Alpert was the “A” in A&M records. He co-owned the label with Jerry Moss (“M”) and served as Vice Chairman (see above). When not busy recording make-out music for tiki bars, he played an executive role and worked with artists until 1993.

It’s true.

Whatever problems country-western music had before circa 1985–which is as good a line to draw as any, I suppose–at least it was, sort of, authentic. These were the songs of angry, disenfranchised working-class white men and they were, if somewhat insular in perspective, still powerful and real.

Now we have this Billy Ray Cyrus mullet hair freakshow posing as the real thing, and it’s this neutered metrosexual garbage about tolerance and compromise and the joys of fatherhood.

Hank Williams is spinning in his grave and the bigwigs at MTV have connected him to a generator and are using him to power the recording studio.

I’m not even a country music fan, and it makes me sick.